Go-arounds don’t have to be hard

Air Facts Journal

“What happened?” It’s the question most pilots dread, because it usually comes from a well-meaning but uninformed person when they read about an airplane crash. Even worse is when the crash involves a celebrity and a small airplane. I shouldn’t be surprised—YouTube is overrun with instant “analysis” videos about every accident, so friends and family expect us all to weigh in with our own opinions—but I still hate it.

So I was a little grumpy when a friend asked me that question a few months ago, in this case regarding the September 18 crash that killed Nashville songwriter Brett James. It’s easy to see why non-pilots might feel confused or even scared when they read news stories like this one from People Magazine (sorry, it was one of the first links on Google) that talk of “the small craft spiraling out of the air.”

The reality is much simpler than most in the media imagine, although certainly no less tragic: it was yet another go-around gone wrong.

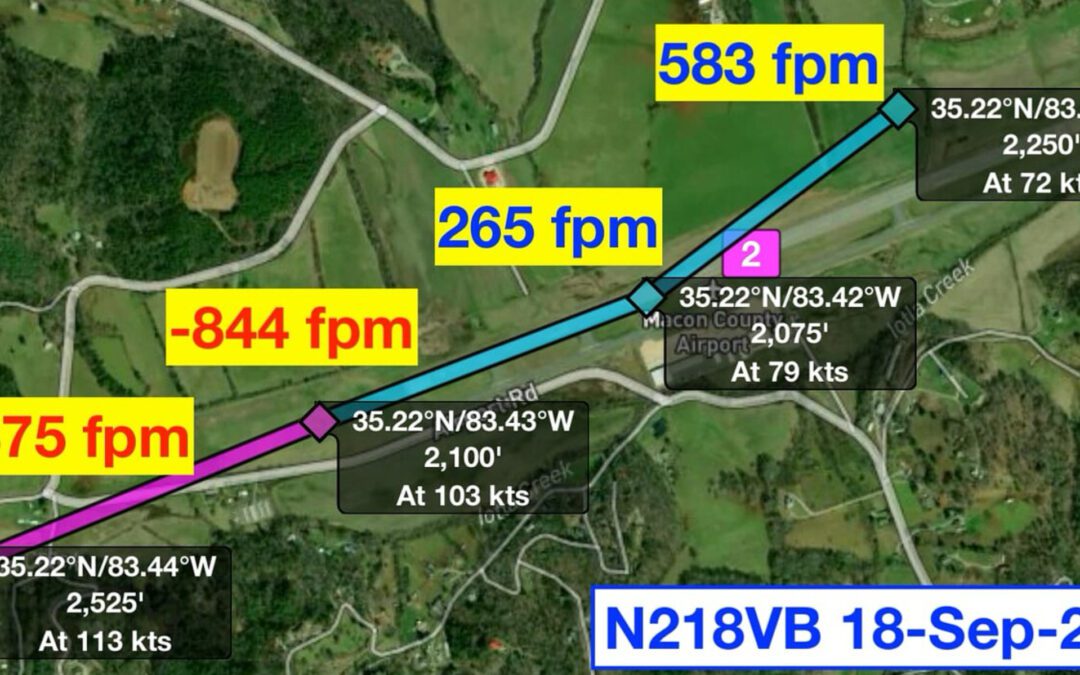

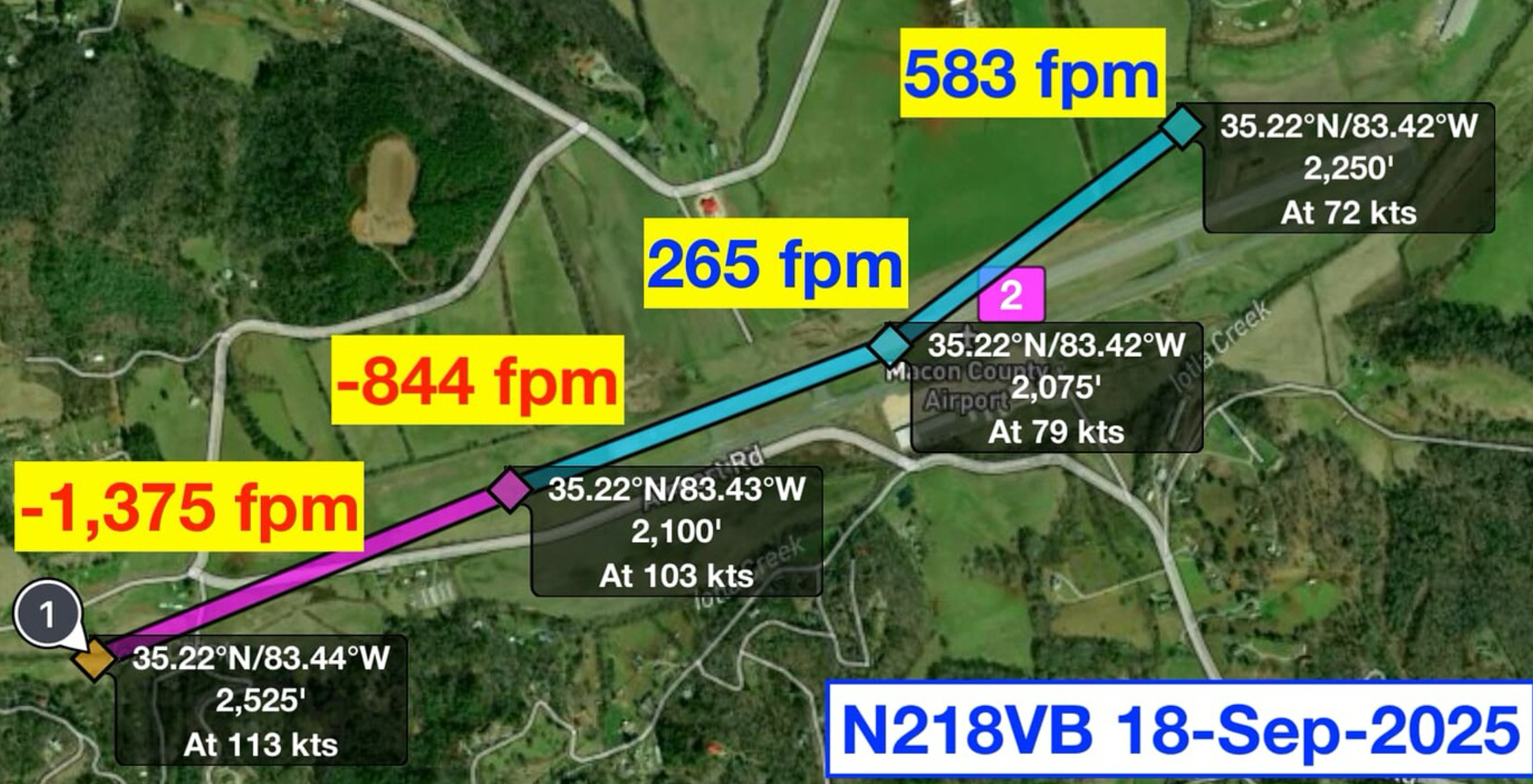

We should wait for the final NTSB report to be sure we know all the details, but the ADS-B data paints an all too familiar picture. The pilot flew an unstable approach, with a high descent rate (nearly 1400 fpm—twice as steep as recommended) and a high approach speed (113 knots groundspeed—easily 25 knots too fast). Recognizing the mistake, he made a smart decision and aborted the landing. But then things unraveled quickly, as the airplane got too slow during the go-around and veered left of centerline. It stalled, started to spin, and crashed, killing everyone on board.

I was grumpy with my friend because I hate the obsession with instant analysis, and he made me participate in this ugly trend. I was grumpy because this accident hit a little close to home, killing a father who was flying his wife and daughter in a Cirrus SR22 (something I do often). But I was mostly grumpy because go-around accidents happen far too often—and they are eminently preventable. This is one problem we should be able to solve.

Defining the problem

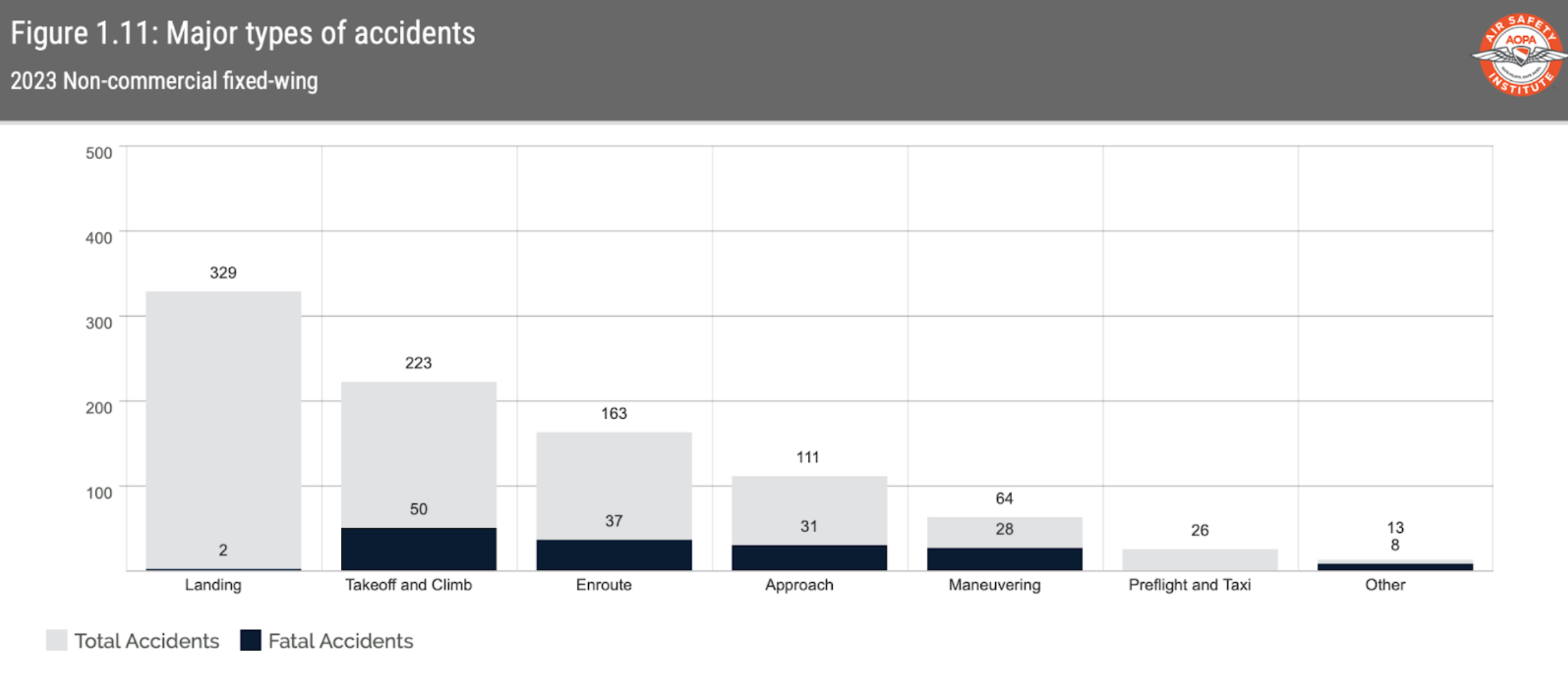

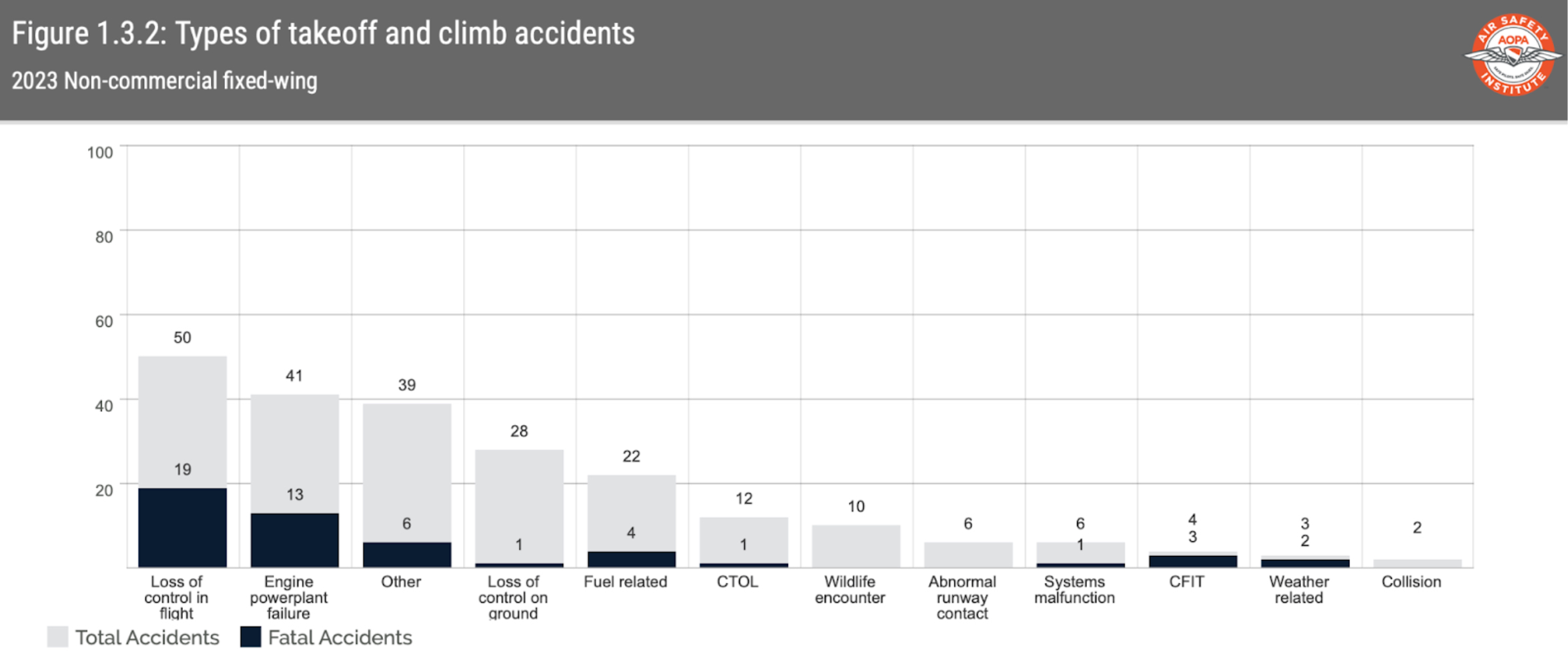

The latest McSpadden Report from the AOPA Air Safety Institute shows reasons for both hope and worry. The overall safety trend is positive, with the general aviation accident rate down 27% since 2014. That is huge progress (and the subject for another article ), but some accident types seem resistant to this progress, like go-arounds. While landing accidents make up more than half of all accidents, they are rarely fatal. Takeoff and climb accidents (where go-around accidents usually get assigned), are less common than landing accidents but far more likely to be fatal. In fact, it’s the leading phase of flight for fatal accidents.

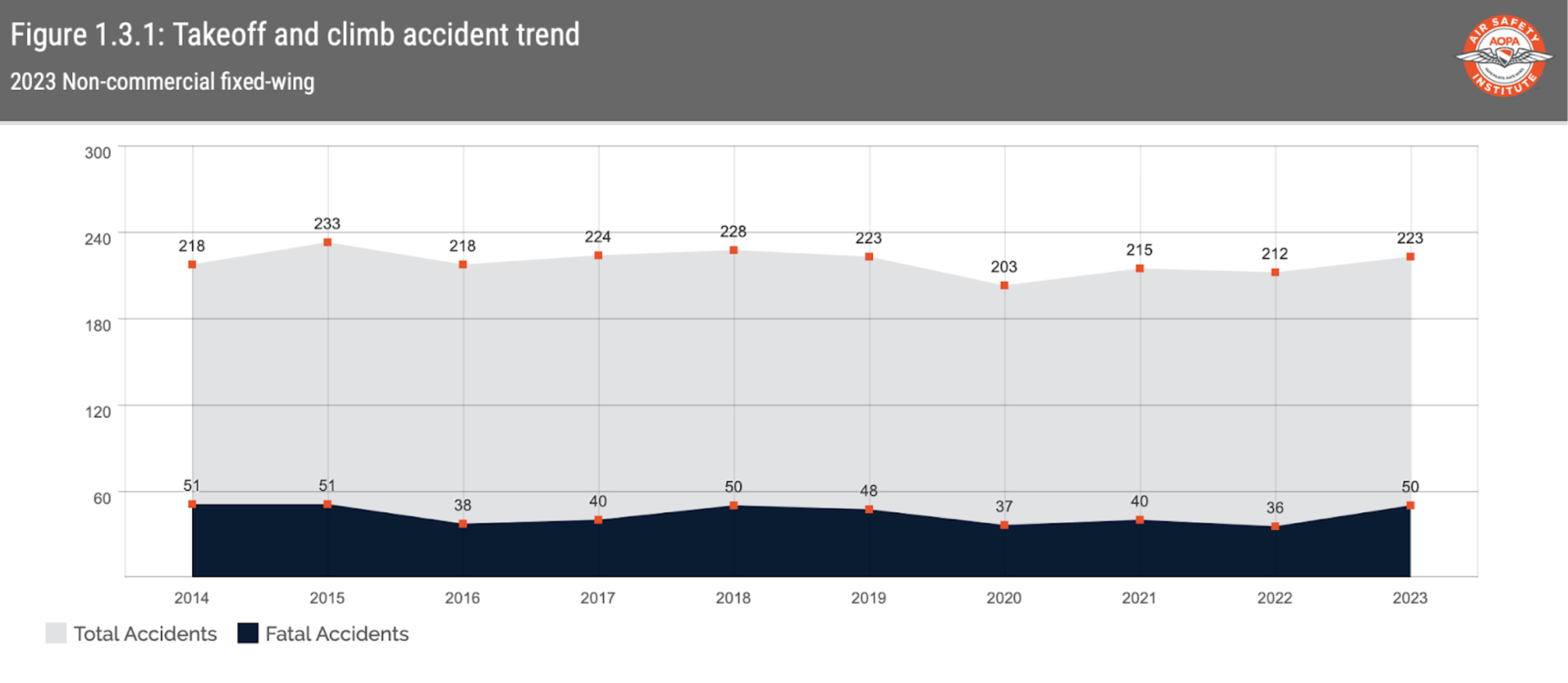

The trend for these accidents is not encouraging, as they are essentially unchanged over the last decade while other categories decline. We can debate whether technology has improved safety in some areas (I think it probably has), but in this phase of flight the answer is a resounding “no.”

What happens during these takeoff and climb accidents? Loss of control is the leading cause. It’s worth reiterating that not all of these are go-arounds—in fact, most of them are not—but there’s clearly something going wrong with pilots’ ability to maintain control during initial climb.

This isn’t a weather issue, by the way, as 94% of takeoff and climb accidents happen during day VMC conditions. It’s also not really a matter of pilot experience: 44% of these accidents had a Commercial or ATP on board.

More granular studies show that go-around accidents have in fact increased over the last two decades. Even more damning, a detailed report from the Flight Safety Foundation shows that even professional pilots struggle, with only 3% of unstable approaches leading to a go-around, and some of those coming too late. We seem to hate go-arounds, and then we stink at them if we do one. That’s a vicious cycle.

Go-arounds are a particular problem for pilots of high performance airplanes—the NTSB reports are filled with SR22s, Bonanzas, and single engine turboprops losing control. This is hardly surprising, since these airplanes have high horsepower engines that put out lots of torque at full power. They also have faster cruise speeds, so it’s much easier to be fast and high on final, causing a go-around in the first place.

How to prevent a go-around

Those unstable approaches are a great place to start our work, because you can’t have a go-around accident if you make a safe landing. I’m in no way arguing that go-arounds are bad, and sometimes you have to abort a landing for reasons beyond your control, but we should acknowledge that many of these tragedies are downstream from our inability to fly consistently good approaches.

Some pilots get very particular about the definition of “stable approach,” and airlines have black and white rules for when an approach should be discontinued. That’s fine for larger airplanes, but I think most GA pilots should focus on one thing: airspeed control. The ability to fly the correct approach speed (ideally to within +/- 5 knots) is the single best predictor of a safe landing, and a skill that translates to almost all phases of flight. It takes practice, but is hardly difficult if you focus on it.

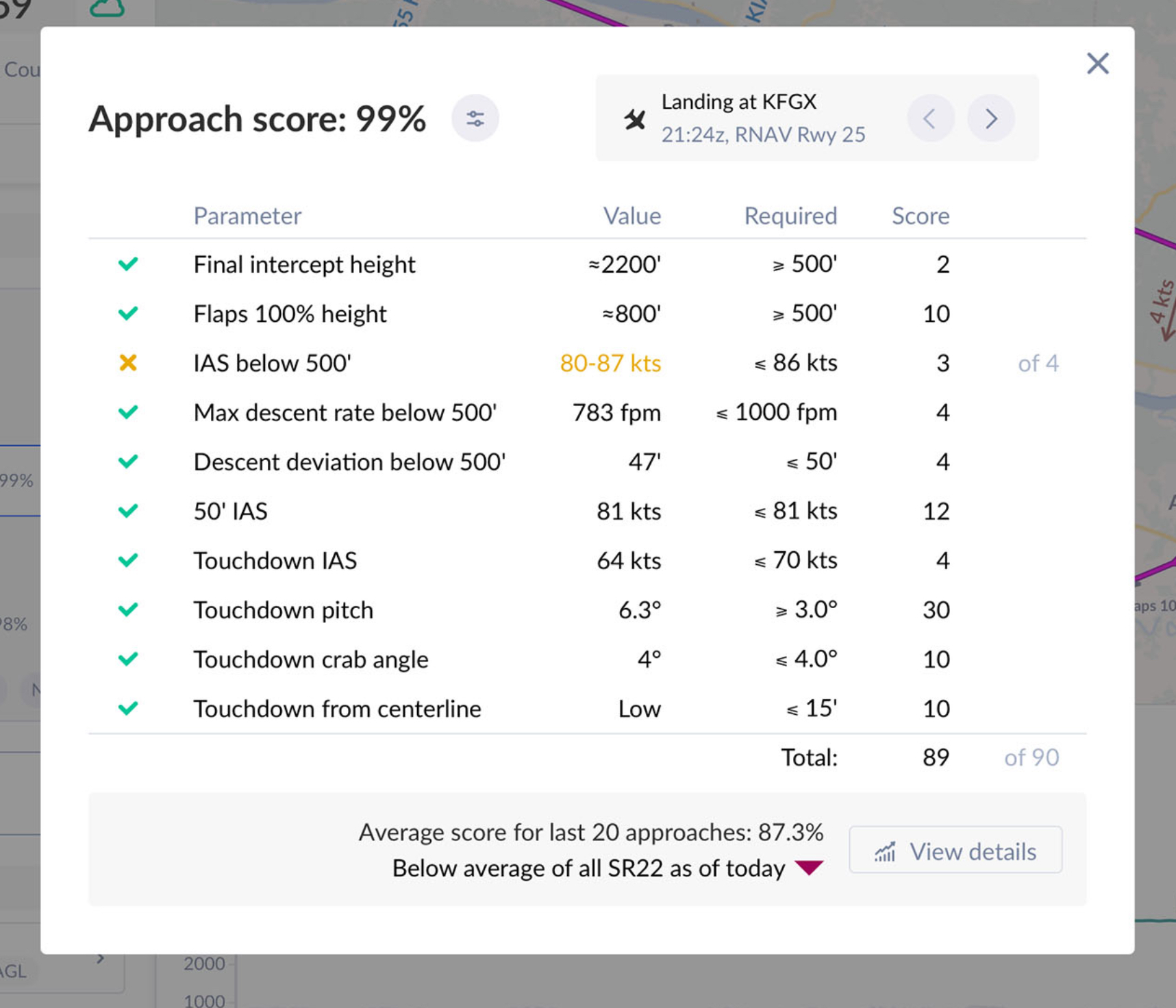

This is now easier than ever, thanks to the latest generation of flight debrief software. Both ForeFlight and FlySto offer affordable and nearly automatic tools for scoring your flights on a range of metrics. You can record data either with glass cockpit avionics like the G1000 or portable ADS-B receivers like the Sentry Plus.

I’ve been particularly impressed with FlySto , which delivers an approach score for every flight that summarizes airspeed control, descent rate, pitch angle, and centerline drift. It even compares your flight to an average of other FlySto pilots who fly the same aircraft type. There is nowhere to run and nowhere to hide with this free app: if you flew a bad approach, you will see it clearly.

Once you have this data, it’s much easier to practice the things that really matter. If you’re struggling with airspeed control, spend some time on slow flight or constant airspeed descents.

How to fly a safe go-around

Even with the best airspeed control, go-arounds are sometimes unavoidable (my last “real” one was caused by a group of deer on the runway, who were totally unconcerned about my approaching airplane). So if you do have to go around, the Flight Safety Foundation report suggests the sooner you decide the better; most pilots probably feel more comfortable making a go-around from 300 feet than 30 feet. Either way, this is a time to be decisive. With extremely rare exceptions, there is no time to change your mind once you add power and start to climb. Forget trying to “save it” and focus on aircraft control.

Breaking it down a little more, a good go-around involves five steps. Each one, and how it’s performed, matters.

1. Add power—smoothly. Just like legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden used to say, “Be quick, but don’t hurry.” In other words, you want to push in the throttle and start climbing as soon as you can, but no sooner. Many go-around accidents are caused by a near-panicked reaction from the pilot, with a rapid increase in power that leads to a rapid increase in torque and p-factor. There’s nothing stabilized about this type of flying. Cirrus advises that pilots should take four to five seconds to add full power on the takeoff roll; something similar is good advice for go-arounds.

2. Pitch up—but not too much. Step two seems so simple, but it’s often where the accident chain begins. A typical NTSB report reads: “the pilot appeared to initiate a go-around; the engine power increased, the airplane’s nose pitched up sharply, the left wing dropped.” The key word here is “sharply,” because that causes a rapid loss of airspeed (especially with full flaps), from which a recovery becomes nearly impossible. Learn what a typical climb attitude is in your airplane, both for takeoff and for go-around configurations, so you have a specific number to aim for. In most GA airplanes that will be around 10 degrees, and yet many NTSB reports show the accident pilot pitched up to 20 or even 30 degrees—a dramatic and disorienting view out the window! Trim plays a critical role here, because full flaps and full power with trim set for landing can create a powerful back pressure on the yoke. Be prepared to push forward and start trimming nose-down.

3. Push the rudder—hard. Have you ever been scolded by an old-timer about lazy feet? It’s no fun, and I have a pretty low tolerance for speeches about “back in my day,” but they are absolutely correct on this one. The critical mistake in most go-arounds, the one that gets pilots killed, is lack of right rudder to offset the increase in engine power. If you doubt me, just read some accident reports: the crash site is always to the left of the runway. Modern airplanes will tolerate uncoordinated flight pretty well, but not with full power and low airspeed. Certainly a tailwheel rating or a glider certificate is a great way to improve your rudder skills, but even simpler is to imagine your right foot being connected to your right hand: when your hand goes forward to add power, so does your right foot to add rudder. If your airplane has a yaw damper, turn it off once in a while and practice adding rudder during a full-power climb.

4. Retract the flaps—but not too fast. If you’ve smoothly added power, pitched up to your target attitude, and kept the airplane coordinated with right rudder, there isn’t much more to do. Yes, you’ll want to get the flaps up, but there really isn’t a rush. Airplanes can and do fly with full flaps, so unless you’re in an old Cessna with 40 degrees of flaps on a 110-degree day, make sure the airplane is stable and accelerating before you make any configuration changes. When you do, avoid the temptation to retract the flaps all at once. Most airplane checklists suggest changing one flap setting at a time and not fully retracting them until clear of obstacles. Dumping all the flaps right at the moment you pitch up can lead to a nearly instant stall.

5. Turn—only when things are stable. One final step is one should not take: turn. If you’ve just aborted a landing and are climbing, there’s no reason to make a turn until everything is stable and the airspeed is safely at or above Vy. Stall speed increases rapidly as bank angle is increased, so take that variable away entirely. Turns, talking to ATC, and checklist usage can all wait. Fly the airplane.

Practice can make perfect

Reading this five-step process makes a go-around sound easy, and it definitely can be—but only if you practice. That’s something that doesn’t seem to happen very often once the Private checkride is complete. Fortunately, go-arounds can be practiced in any airplane and on any flight, and can easily be integrated into a flight review or instrument proficiency check. The key is to make these scenarios realistic, in particular with some element of surprise. A real go-around will probably not be one you expect, and you may not like your performance as a result.

Consider one go-around accident that was caused by a pilot’s confusion, probably due to a large dose of adrenaline: “During the go-around, the pilot initially thought he had pushed the throttle control full forward, but when ‘nothing happened,’ he looked down and realized he had pushed the mixture control forward.”

Eliciting a reaction like that requires another pilot or a flight instructor in the right seat, one with some creativity. My favorite tip came from a particularly devious flight instructor who got to know the controllers at a nearby Class D airport. He would call the tower before a training flight and tell them to surprise the pilot with a go-around at some point during landing practice. Hearing it from ATC instead of your right seater, and having it be truly unexpected, is great practice.

Go-arounds are the ultimate example of an easy but unforgiving maneuver. The good news is, the more comfortable you are with go-arounds, the more likely you are to do one when needed.

The post Go-arounds don’t have to be hard appeared first on Air Facts Journal .